12 Angry Men: A Subversive Masterpiece

Analyzing the themes of morality in the classic courtroom drama 12 Angry Men.

The 1957 courtroom drama 12 Angry Men is widely considered to be one of the best films ever made. The movie’s premise is that an 18-year-old boy is on trial in New York City for first-degree murder in the stabbing death of his father. If found guilty, he is to be sentenced to death. Other than brief opening and closing scenes, the entire movie takes place in the jury deliberation room. Twelve nameless jurors argue back and forth over whether or not the accused is guilty of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt as the decision to either convict or acquit must be unanimous.

At first, it appears to be an open and shut case in favour of a conviction. However, when they take a preliminary tally, one juror dissents against the consensus of “guilty” and votes “not guilty”, not wanting to send a boy to the electric chair without having had a discussion about it first. The other jurors are initially surprised, confused, or annoyed that the decision to convict isn’t unanimous, but as doubt is cast upon the each of the inculpatory pieces of evidence, one-by-one they switch their votes from “guilty” to “not guilty”. After an hour-and-a-half of fiery debate, they arrive at a final verdict of “not guilty”.

Unlike the typical Hollywood movie about a larger-than-life gunslinging hero embarking on an extraordinary adventure, 12 Angry Men features a group of men with ordinary jobs sitting around in a room discussing the intricacies of a legal case. The characters start off as random nondescript faces, but over the course of the film, each of their unique multi-layered personalities are revealed as they clash with one another over their conflicting perspectives on the case. What makes 12 Angry Men such a praiseworthy film is levels of heart-stopping drama it is able to create with an extremely simple concept.

The American Film Institute included 12 Angry Men at #87 on its list of the top 100 best films of the past century in 2007. The movie has a near perfect rating on sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic and was selected for preservation by the US Library of Congress for its cultural and artistic significance. Though I maintain that 12 Angry Men is an extraordinary work of drama, when analysing the morality preached by the film, I can’t help but see the underlying messages as subtly pernicious.

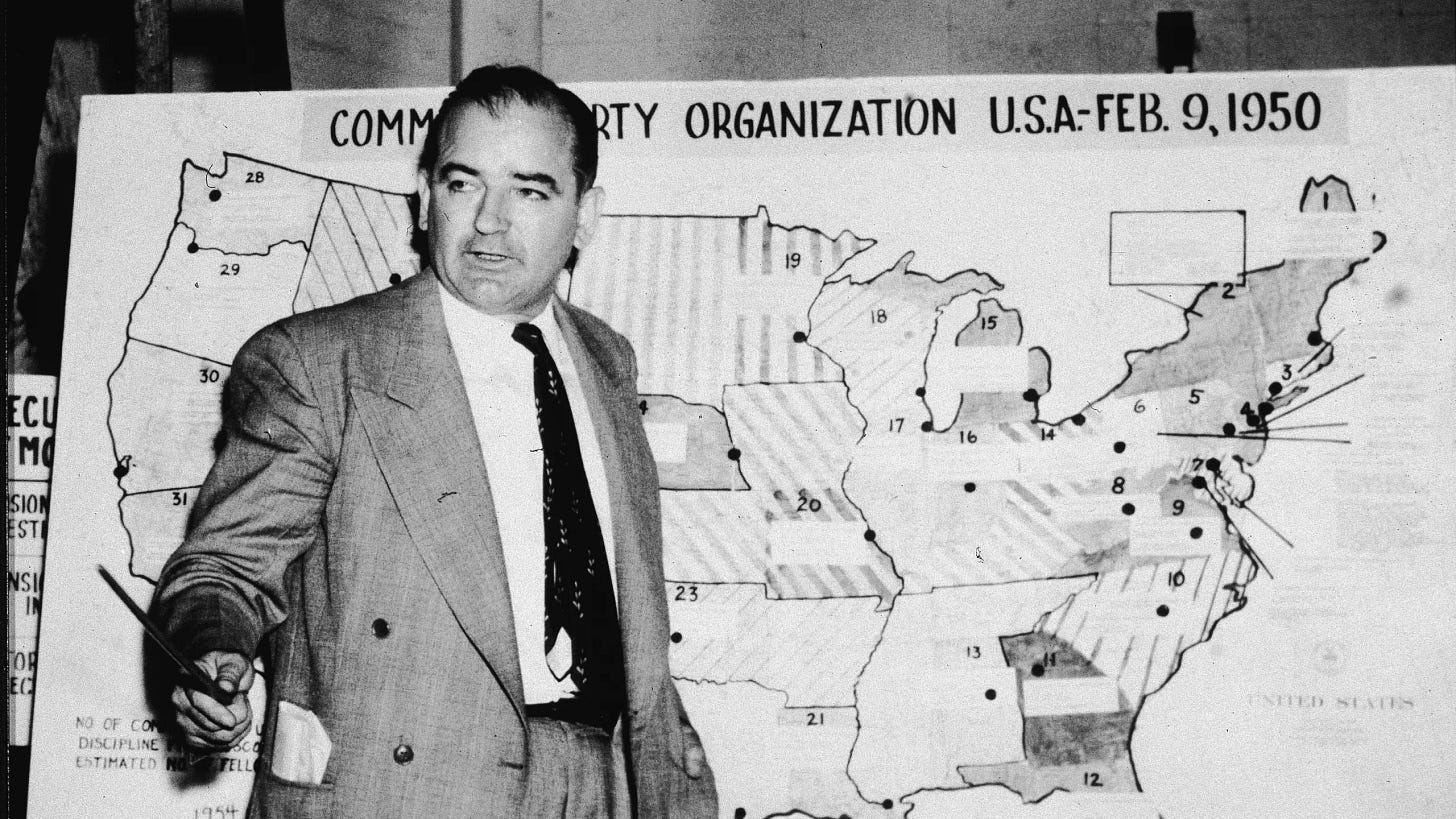

For some further context, 12 Angry Men was the first film directed by Jewish filmmaker Sidney Lumet and released in 1957 during what was known as the McCarthy Era or the Second Red Scare in the United States. This period throughout the 1940s and 1950s saw a number of figures in Hollywood blacklisted for allegedly holding communist sympathies after the industry came under political scrutiny, mainly from the House of Un-American Activities Committee. 12 Angry Men is often interpreted as a critique of the “lynch mob” mindset behind the ostracization of members of the entertainment industry during the McCarthy era.

One extremely effective storytelling device employed in 12 Angry Men is that the truth of the accused’s guilt or innocence is never revealed. Like the twelve jurors, the audience are only privy to the evidence which had been presented during the offscreen trial. Rather than a debate on the likelihood of the boy’s guilt in reality, the debate is over whether or not he has been proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt as is the standard required for conviction under American law. With this in mind, I still find the jury’s verdict of “not guilty” highly questionable.

The prosecution’s case alleges that the boy and his father got into a heated argument during which his father struck him twice, prompting the boy to yell “I’m going to kill you!”. The boy left the home, purchased a very unique switchblade from a pawnshop, and returned to stab his father to death. A woman in an apartment across a set of tracks witnessed the murder through the windows of a train car and the boy was seen fleeing down a staircase by an old man in the apartment below. The presumed killer returned to the home several hours later where the police were there to make the arrest.

The defence’s case alleges that the boy left his father’s home following the argument and went to the movie theatre for several hours. The boy admitted to purchasing a switchblade similar to the one used in the crime, yet he alleges that he lost it through a hole in his pocket. He returned home several hours later to find his father dead. The prosecution retorts that the boy was unable to recount details from the movies he had allegedly just finished watching when interviewed after returning to the scene and no witnesses nor additional evidence such as ticket purchases could place him at the theatre.

Over the course of their deliberation, the jury find cause for reasonable doubt with both the witness testimony and the circumstantial evidence. They reach the conclusions that the woman couldn’t have positively identified the boy since she had marks on her nose which indicated she wore glasses, which she wouldn’t have worn to bed. They conclude that the old man living on the floor below was too slow to have been able to reach the door in time to see the boy fleeing the scene. They theorize that phrase “I’m going to kill you!” might not have indicated an intention to commit murder as it is often used rhetorically.

For the circumstantial evidence, one juror found a knife for sale matching the one used for the crime in the same neighbourhood, meaning it wasn’t one-of-a-kind. They conclude that since the accused was handy with a switchblade, he would have used an upward stab rather than the downward one which was inflicted against his father. They deem his alibi plausible because it’s possible that he may have forgotten details about the movies he had just seen due to the high degree of stress he was under upon being accused of murder.

While the jurors succeed in arguing that the prosecution hadn’t proved the defendant guilty with 100% certainty, if we are to consider 90% or even 95% certainty to be beyond a reasonable doubt, I still believe that the prosecution has surpassed that threshold. The dismissal of the witness testimony is based on very selective speculation. It’s possible to come up with a number of speculative scenarios which would explain why their testimony was valid such as the woman being farsighted or the old man having made for the door a few seconds earlier. It’s possible for a witness to be mistaken, but it’s less likely that two would have both been mistaken, especially when they have no incentive to lie.

But even without the witness testimony, the circumstantial evidence in this fictional case should’ve been enough for a conviction. It may be hypothetically possible that an unknown intruder stabbed the father to death in his home after he had had a heated argument with his son using the exact same kind of knife his son bought then lost that same night. However, the likelihood of such a coincidence in comparison to the son being the killer, in my estimation, is less than 1%. The fact that the boy had a history of violence perpetrated using a switchblade is a lot more incriminating than the fact that the death blow was in a downward motion as opposed to an upward one is absolvitory.

Not only the amount inculpatory evidence, but also the lack of exculpatory evidence would convince me of the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. There really is no alternative theory of the crime. There was no forced entry into the apartment, nor anything reportedly stolen. There are no alternative suspects who had a motive to murder the man. The boy being unable to recall details from the movies he claims to have just watched may not disprove his alibi, but there is no evidence to verify his alibi either. The absence of any witnesses placing him at the theatre or a ticket stub to substantiate his claim that he had been there means his alibi is most likely false.

I understand that the debate isn’t over whether or not it is more likely that the defendant is guilty on balance of probabilities, but if he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Though the standard of reasonable doubt exists because one can never be proven guilty of a crime with 100% certainty. The fact that it’s simply imaginable that one is not guilty cannot be sufficient to constitute reasonable doubt and secure an acquittal. Under that standard, it would be impossible to convict anyone of any crime.

Now, 12 Angry Men is a fictional movie, not a real legal case. It may seem that I am overanalysing the minute details of an old film, but when considering morality it preaches, the faulty reasoning behind the verdict cannot simply be written off as dramatization for the purposes of storytelling. To understand the underlying message of the film, it’s important to look at how the characters in the story and ultimately the viewers themselves are persuaded of a “not guilty” verdict, because it’s not on the basis of the evidence.

The defendant in the plot is described as being a disadvantaged 18-year-old boy living in a slum in New York City with his abusive father. It doesn’t clarify his ethnic background, but he is referred to as an outsider from America’s WASP majority at the time, possibly an Italian or Puerto Rican. The hero of the film is Juror #8, brilliantly portrayed by legendary actor Henry Fonda. He is the only one to dissent against the initial consensus and vote “not guilty”, making the vote 11-1. While he is unsure of his decision, he does so out of a feeling of sympathy for the defendant due to the hapless circumstances of his upbringing.

The villains of the film are Juror #3 and Juror #10, the two most adamant advocates of a “guilty” verdict. Over the course of the film, their biases against the accused are revealed. Juror #10’s insistence on a “guilty” verdict is influenced by a deeply held prejudice against the unnamed ethnic group the boy belongs to, referring to him as “one of them”. Juror #3 remains the last one out of the twelve to obstinately maintain a “guilty” vote because he subconsciously sees the case as a proxy for getting revenge on his own estranged son who assaulted him after the two had a falling out.

The film gets the audience to sympathize with the defendant by painting him as a “victim” through the lens of Marxian critical theory. The emphasis on his socio-economic status, his ethnic background, and his relationship with the patriarch of his family establish him as a member of an underclass who have supposedly been wronged by society. As the jurors switch their votes from “guilty” to “not guilty”, the viewer is given the perception of a moral consensus that such a worldview is correct and just.

The movie does this effectively by presenting Juror #8 as a morally upstanding and humane everyman who just wants to do the right thing in good conscience. It’s worth noting that Henry Fonda was one of the most famous stars in Hollywood at the time and known for playing the archetypal “good guy”. Apart from Lee J. Cobb and Ed Begley playing the villains, the rest of the cast were relatively unknown, meaning a 1950s audience would immediately identify with Fonda’s character above the others. In contrast, Juror #3 and Juror #10 are presented as cruel, boorish, and ignorant, making their arguments for a “guilty” verdict unconvincing, regardless of the facts.

While this doesn’t answer the question as to whether the boy is guilty or not, this framing heavily biases the viewer towards the “not guilty” camp as it is established in their mind as the morally just position. At the conclusion, the ardent proponents of a “guilty” verdict are shown to be influenced by prejudice rather than evidence, but the same can be said for many of those who come to support a “not guilty” verdict.

Juror #9 changes his vote from “guilty” to “not guilty”, not based on the evidence presented, but because he views Juror #8’s cause as righteous. It is revealed that Juror #5 grew up in a slum and is offended by Juror #10’s derogatory remarks about the ethnic background of the accused. He changes his vote from “guilty” to “not guilty” because he identifies with the boy, having grown up in similar circumstances. Juror #5’s sympathy with the boy is portrayed as empathetic. Although Juror #3 is the primary antagonist of the film, his motivation could be interpreted as empathetic towards the victim since he too had been violently victimized by his own son. However, he is portrayed as calloused rather than compassionate.

Juror #10, the secondary antagonist, is portrayed as a bigoted racist whose staunch “guilty” vote is motivated by his prejudice against the ethnicity of the accused. Yet it is established that the boy had a history of violence and that the neighbourhoods populated by this unnamed ethnicity have high levels of crime. Juror #10’s motivation is represented as ignorant and discriminatory, but even within the film’s own narrative, his preconceptions of the defendant as having a propensity for violence have some basis in reality.

To the film’s credit, it addresses some of the counterpoints to the “not guilty” camp. Juror #8 contemplates the possibility that his vote could be allowing a murderer to get away with his crime. Juror #7 is more interested in the baseball game he has tickets to than the case and simply wants to get the process over with as soon as possible. At the start, he votes with the consensus of “guilty” when it was 11-1 but then switches his vote to “not guilty” when it is deadlocked at 6-6, not because he had changed his mind, but because he hopes it will speed up reaching a final verdict.

Juror #7 is chastised by Juror #11, who had also voted “not guilty”, for basing his vote on his own personal convenience rather than a regard for justice. This exchange also introduces another subversive theme into the story. Juror #11 reveals he immigrated to the United States as a refugee from Europe. His exact background isn’t clarified either, but he could be interpreted as being Jewish. He is portrayed as being more educated, enlightened, and devoted to the ideals of the American justice system than most of the native-born jurors. This shifts moral standing away from the WASP majority and towards another out-group. It’s also possible that director Sidney Lumet used Juror #11 as a proxy for himself in American society, given his background.

Juror #4 is shown as the most objective and analytical of the twelve. He is the least emotionally invested in the verdict and is solely focused on whether or not the defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. He is one of the last to change his vote from “guilty” to “not guilty”. This adds a seal of objectivity to their final verdict of “not guilty” and reveals the final holdout, Juror #3, to be motivated by a personal vendetta. This misleads the audience into believing that the “not guilty” verdict is objectively correct when, as stated earlier, the case for the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt remains far more convincing in my opinion.

One element of human nature which 12 Angry Men illustrates extremely effectively is that everyone is biased in some way. The issue is that the film portrays bias in favour of a purported underclass as identified through the framing of critical theory as moral and bias in the opposite direction as immoral. And the film does this tremendously well. I only came to the conclusion that the verdict reached in the movie was incorrect after detaching myself from the story and attempting to analyze the facts of this fictional case as objectively as I possibly could.

During my first viewing of the film, I was franticly hoping for a “not guilty” verdict. Even now, after having come to the conclusion that the verdict was wrong, I still get a residual sense of wrongdoing in taking that position, as if I’m being cold-hearted and cruel. That’s a testament to the power of moral consensus. One will disregard all objectivity if it could lead to them feeling like a bad person in the eyes of those around them.

Why do liberals believe that Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Karmelo Anthony, and Christopher McCowen are victims of “institutional racism” and rather than offenders? It’s not because they have objectively considered the evidence in each of these cases and come to the well-reasoned conclusion that they did nothing wrong. It’s because they’ve been told that holding these beliefs is the morally correct position by the media, the highest moral authority in the modern world. So they twist themselves into pretzels to make these postulations make sense in their mind. This is the moral framework eroding Western society today, one of the early purveyors of which was 12 Angry Men.

Unlike present-day propaganda which is preachy, on-the-nose, and inane, 12 Angry Men is effective. In addition to being an outstanding work of drama, the film puts forward its messaging subtly, but successfully. Henry Fonda’s character, Juror #8, comes across as genuinely heroic and you leave the movie with a sense that justice has been done. However, by then you have forgotten that someone was murdered and no longer consider the possibility that the killer has just escaped justice and may go on to kill again, the likelihood of which is significant.

Only a decade after the release of 12 Angry Men, Lyndon Johnson, the president of the United States, more or less blamed the black riots of 1967 which caused dozens of deaths and thousands of injuries on the “racism” of white Americans. He posited that, while he doesn’t support lawlessness, those burning down dozens of cities across the country were actually victims driven to violence by such injustice. This sentiment would’ve been considered ridiculous in decades prior, but by then, this was the new moral consensus in America which Hollywood played a pivotal role in forming.

Sidney Lumet went on to direct The Pawnbroker, one of the first movies to push guilt over Jewish suffering during the Holocaust. It was also instrumental in overturning the Hays Code, allowing Hollywood to produce much more overtly sexualized media. He also directed Dog Day Afternoon, a movie about a pair of homosexual bank robbers attempting to pay for a gender reassignment operation, decades in advance of the recent attempts to normalize such a thing. He later made Daniel, a film which lionizes Jewish communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Nothing of the sort is featured in 12 Angry Men, but Lumet’s later work gives an insight into the mind behind the much renowned classic courtroom drama.

The story we are told about the McCarthy era today is that it was a paranoid witch hunt which unjustly tarnished the careers of filmmakers in Hollywood with baseless accusations. 12 Angry Men has been interpreted as a rebuttal of McCarthyism, but does it not serve to prove the fears of people like McCarthy valid? Firstly, the fact that the supposed victims had the ability to produce movies about their own victimhood proves that they weren’t powerless underdogs up against the establishment, but that they were the establishment. Secondly, when you consider the worldview which Hollywood played a vital role in promoting and the impact of such ideas in the present day, it’s hard not to see their influence as hostile.

12 Angry Men is the story of a murder trial in which the case for a “guilty” verdict appears clearcut at first, but after a long and strenuous debate, concludes with a final verdict of “not guilty”. However, I’d argue that this conclusion isn’t a result of evidence-based fact, but of the perception of moral consensus. This manipulates the viewer into believing the case for acquittal is a lot more convincing than it should be. Perhaps, the same can be said of the established narrative on this period in history. Was acquitting those accused of malevolent subversion back then the correct verdict or have the decades since shown that they really were guilty as originally charged?

Thank you for this. I'd like to think for each thread of Marxist propaganda you help me untangle eventually the entire tapestry of indoctrination will unravel. I watched this in a class in middle school, then in a class in high school, then in a class in college. When my girlfriend, now wife, said she had not watch this, we rented it and watched it together.

It’s the same with “classic” books such as Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Lord of the Flies. Lefties, led mostly by jews, only add such stories to the canon in order to critique and undermine the West, not because they are great literature.