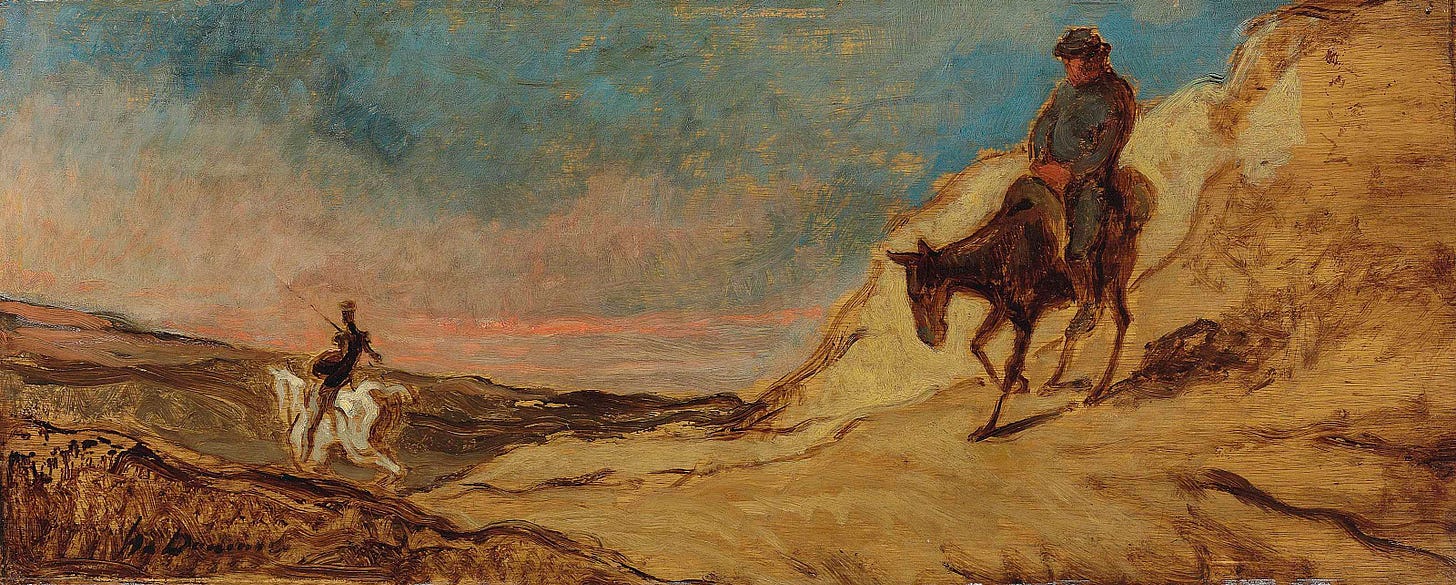

Last year, I wrote a series of essays inspired by Don Quixote, the two-volume 17th century novel by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. Don Quixote, the titular character, is a fictional Spanish knight who, driven mad by his obsession with tales of knightly chivalry, goes out into the world on an adventure in pursuit of his ladylove Dulcinea Del Toboso, a romanticized figment of his imagination. The character Don Quixote inspired the creation of the word “Quixotism” which is used to denote naïve idealism without any regard for practicality. My series was titled The Folly of Quixotism and focus on how devotion to ideals beyond all practicality can and has derailed political movements.

But what would be the opposite of Quixotism? In the novel, Don Quixote is accompanied by his so-called “squire”, Sancho Panza, a fat old servant who Don Quixote persuades to join him on his misadventures with the vague and empty promise of making him the governor of an island. Sancho Panza is the antithesis of Don Quixote. While Don Quixote sees the world through an overly romanticized idealistic fantasy, Sancho sees the world as vapid and banal, without any enchantment to be found anywhere.

This word hasn’t been widely adopted into the English lexicon, but some have referred to the opposite of Quixotism as “Panzaism”, denoting soulless practicality without any regard for idealism. Sancho Panza is well aware that Dulcinea Del Toboso, the love of whom his master relentlessly seeks, doesn’t actually exist. Why then does he agree to accompany Don Quixote on his adventure? Prior to becoming Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho lived a rather depressing life with an unattractive hag of a wife, as cynical and contemptuous as him. It’s not the adventure he finds alluring. It’s the hope, albeit a faint one, that he will receive some kind of material benefit which will pull him out of the dreadful life he had prior.

Much of the comedic farce of the novel is derived from the clash between the antithetical characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Sancho is begrudgingly dragged along on Don Quixote’s delusional pursuit of his misguided ideals of knightly chivalry, moping in his own misery the whole way. But through a series of comedic mishaps, Sancho eventually finds himself being made the governor of an island, as Don Quixote had promised him. However, once he finally attains this position, he realizes that he’s unhappy with his reward and decides to return to his role as Don Quixote’s squire, missing the adventures the two had together.

By the end of the novel, Don Quixote is snapped out of his bout of insanity and realizes the foolhardiness of his romantic idealism while Sancho Panza evolves out of his nihilistic cynicism and gains a sense of transcendence and purpose. To borrow a cliché, Sancho realizes that perhaps the real Dulcinea Del Toboso was the adventures they had along the way. My favorite part of the novel was Sancho’s character arch, while I found Don Quixote’s repudiation of his fanciful ideals at the conclusion of the story somewhat disappointing. Don Quixote might have been an insane bubbling fool lost in his own fantasies, but I couldn’t help but like the guy.

He is like an early 17th century version of Mr. Bean. Rowan Atkinson’s performance as Britain’s most famous walking disaster was a smashing success worldwide. Other than the comedic genius of the sketches, everyone seems to love the character of Mr. Bean himself. Why is that? Not only is Mr. Bean socially inept and odd, but he’s also psychopathically selfish and sadistic, often enjoying being cruel to others. What’s so endearing about him is that he has a childlike infatuation with things like Christmas, candy, comic books, and amusement parks. Mr. Bean sees the world as magical in a way that those around him don’t. While he endures one calamity after another, you never get the sense that Mr. Bean is living an unhappy life.

For a less comedic example analogous to the contrast between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, we can look at David Lean’s 1965 film Doctor Zhivago, in particular the differences between the title character, Doctor Yuri Zhivago and his half-brother Yevgraf Zhivago. Yuri is a starry-eyed visionary who sees the world around him as full of whimsy and enchantment, which he expresses in his poetry. Yevgraf is a single-minded Marxist ideologue whose every effort is devoted to bringing about a socialist revolution in Russia.

At the start of the story, Yuri is a renowned poet and newly made general practitioner in Imperial Russia, set to marry the woman he has loved since childhood. Yevgraf is an ordinary industrial worker and member of the Bolshevik Party determined to see his revolution come into fruition. Following the 1917 Revolution, Yuri finds himself an enemy of the new Bolshevik regime, who view his poetry as “petty bourgeois sentimentalism”. The only time Yevgraf ever goes against the revolutionary cause which he is so loyal to is to help Yuri escape arrest and flee to the Ural Mountains. Though it’s a violation of Bolshevik Party doctrine, Yevgraf keeps an illicit copy of Yuri’s works for himself, finding the poetry captivating.

At the conclusion of the story, Yevgraf is a prestigious officer in the new Soviet regime, having seen his revolution fully realized. In contrast, Yuri ends up as a sickly and dishevelled drifter on the streets of Moscow, having lost the love of not one, but two different women. In practical terms, Yevgraf gains everything while Yuri loses everything. However, when he finds his half-brother in such a seemingly lamentable state, Yevgraf notes that despite it all, Yuri is still happier than most men. Yevgraf is so laser-focused on his political goals that he has very little time for sentimentality, but what he comes to admire in his half-brother is that Yuri is always able to see wonder in the world, even in the worst of times.

How do we see Panzaism playing out in the real world today? In my series on Quixotism, I pointed out that, over the past several decades, conservatives have been so devoted to naïve classic liberal ideals which have rendered them powerless when up against a left that has no interest in playing fair. When we look at the political trends of the past 60 years, it’s clear that over that time, the left has been more successful in shaping Western society. A major part of the reason why is that they have a will to power and are not as hindered by an impractical devotion to principles created for a long-gone era as the right has been during that time.

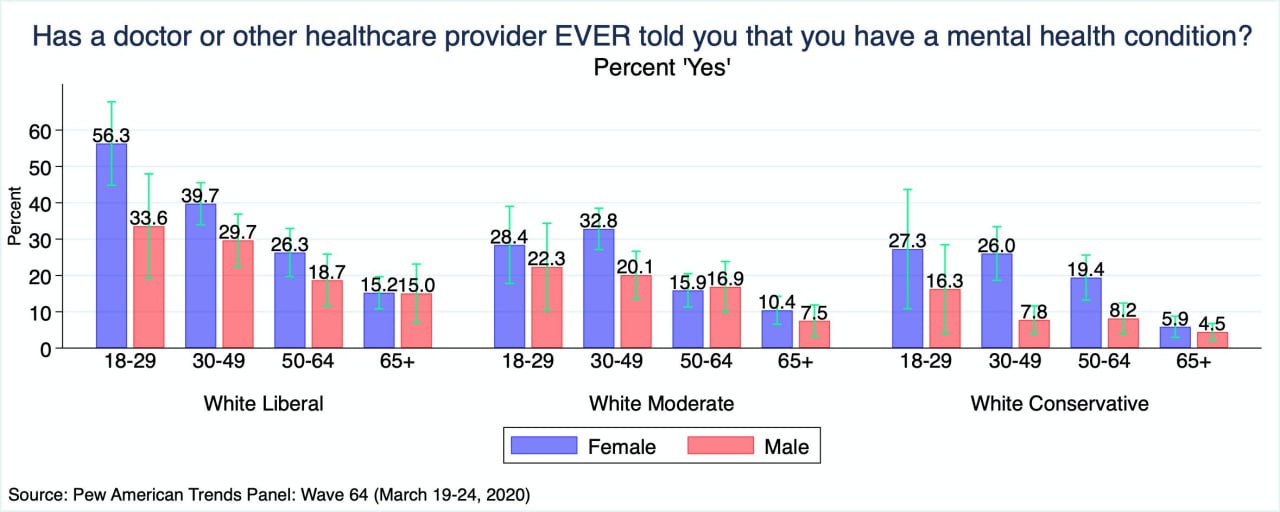

Despite the fact that for decades, the left has been far more successful politically, many studies have shown that on average, conservatives tend to report a greater degree of life satisfaction than liberals. How can this be? If society has been shaped in accordance with their values, why aren’t left-leaning individuals happier in said society? We might not be able to definitively say conservatives are happier than liberals, but some of the research suggests that this could be the case due to higher levels of neuroticism among liberals than conservatives. This could be one factor contributing to the fundamental differences in outlooks between the right verses the left.

The terms “the right” and “the left” as applied to politics originated from the seating arrangements of the National Assembly during the French Revolution. Catholic monarchists sat on the right, secular republican revolutionaries on the left, and moderates in the centre. Though the labels “right” and “left” have been applied to all sorts of political positions in the centuries since, the right has generally taken on the role as the defender of tradition while the left has generally taken on the role of the critic.

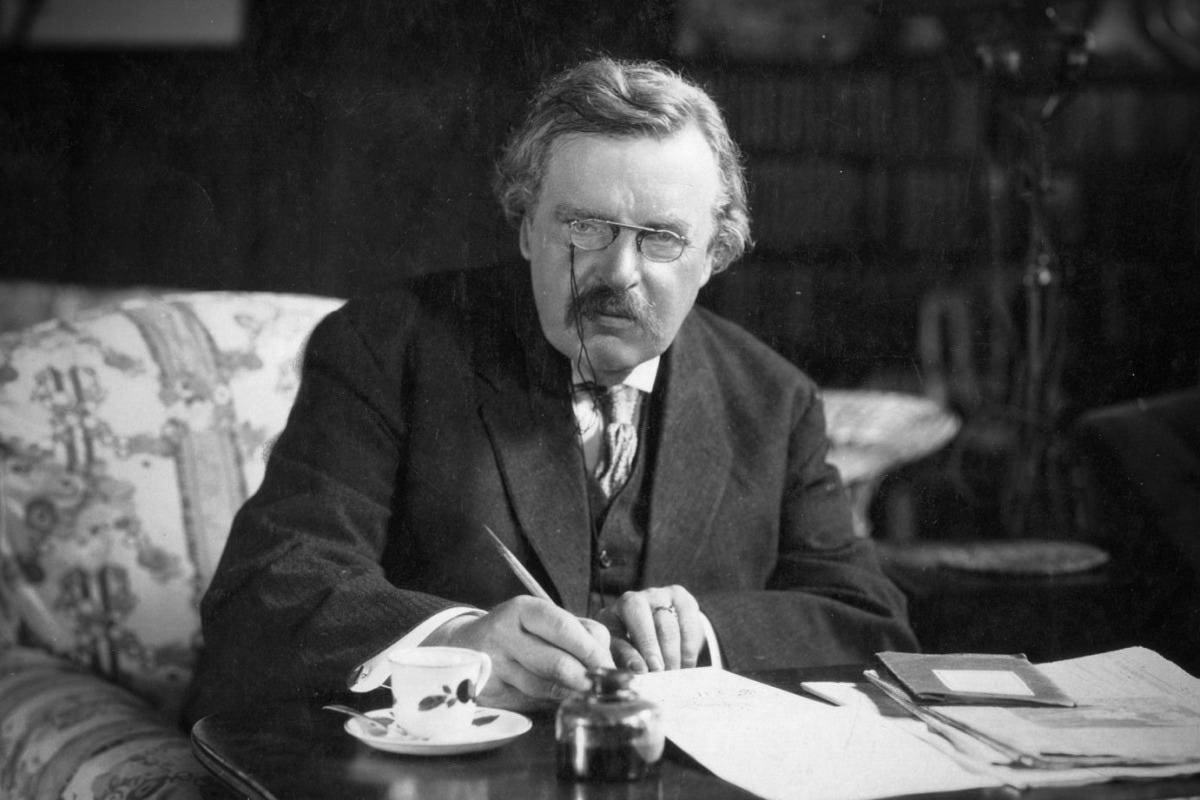

The right has typically valued faith in a god, loyalty to a king, or rootedness in a land and ethnic group and attempted to preserve these foundations, whereas the left has typically found faults in these and attempted to either reform or eliminate them. Regardless of how politically inept conservatism might be in the present day, I would posit that the reason that those who lean right tend to be happier than those who lean left is because they are able to value these in and of themselves without feeling the need to scrutinize and deconstruct them as a more neurotic person would. GK Chesterton said that the true soldier fights, not because he hates what’s in front of him, but because he loves what’s behind him. Fighting for the unconditional love of king and country is more gratifying than fighting for the faint chance that you will be able to find something of value once such institutions are destroyed.

While Don Quixote is an apolitical novel and was written two centuries before these political denominations were conceptualized, the character of Sancho Panza shares an outlook on the world with far-left radicals of the present day. Panza sees no value in the world around him and is simply motivated by the vain hope that his life will get better if he’s given some kind of reward. The Marxist revolutionary has nothing behind him which he loves. He is solely motivated by a hatred of that which is in front of him. His motivation is that he might find fulfilment if his utopian delusions come into fruition. That’s why those fitting this archetype are almost always profoundly miserable people.

Likewise, the character of Don Quixote shouldn’t be described using modern political labels such as “right-wing”. However, in an absurd and farcical way, he considers himself an upholder of the traditional order and a defender of his homeland, La Mancha. The character was written specifically to satirize the virtues of knightly chivalry, yet it’s undeniable that holding such ideals provides Don Quixote with ample motivation on his quests, regardless of how foolhardy that may be.

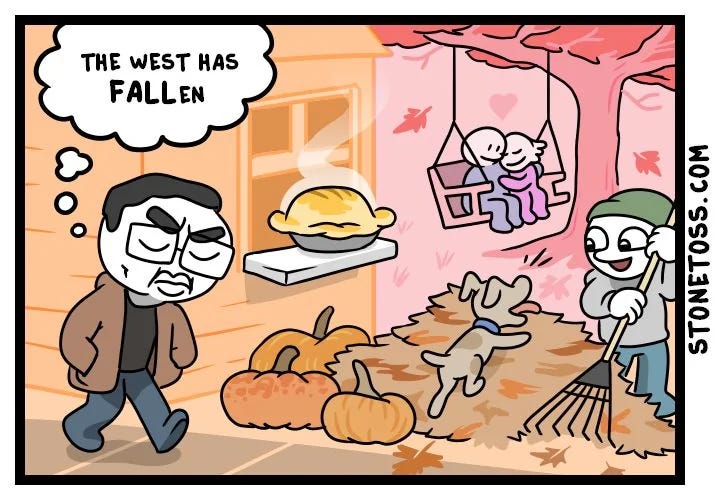

Though the assertion that those on the right tend to have greater degrees of life satisfaction than those on the left could be true, I’ve been in this sphere of politics long enough to know that that there is certainly no deficiency of misery on the right as well. The phrase “the black pill” exists to denote this specific kind of right-wing dejection. To be black pilled is to believe that the political situation is hopeless and that the aforementioned foundations which the right values are lost forever.

I’ve interacted with countless individuals matching this description over the past decade. What I’ve found is that the source of the black pill is never a well-reasoned analysis of the state of the Western world which leads to the objective conclusion that the situation is beyond salvation. The source is always a nihilistic demoralization as a result of a lack of something concrete to provide motivation. Referring back to Chesterton’s true soldier, I’ve always found that the black pill is not the result of the perceived strength of the foe one sees in front of them, but the lack of something one loves behind them.

The black pilled might profess a love for a nation, a culture, a land, or a god, but they don’t conceive of these as concrete entities which exist in reality and ought to be defended. They only envision them in the abstract as some kind of prize they will receive if they are politically successfully. The black pill is the Panzaism of the right. It’s the obsession with the practicalities in relation to the political, preventing one from seeing anything intrinsically valuable in the world around them. Since fulfilment is not derived from politics, these types are always the ones to give up and walk away from whatever cause they profess their devotion to. Despite seeing nothing but the political, the black pilled are politically useless.

The way to avoid Panzaism, or the “black pill” as it is usually called on the right, is to not look for transcendence as some kind of reward for political success. Instead, look for truth, goodness, and beauty in the world as it exists in reality. Your nation, your culture, and your land should not be seen as abstractions which will only manifest themselves once you have achieved political success. They should be a tangible part of your life.

Who are the real, flesh-and-blood people in your life who matter to you? What is something specific about your culture which resonates with you and how does this help shape the life which you live? What is it about your land which makes it feel like home? What are the landmarks, nature, or places you know personally which give you a sense of belonging? If you don’t have answers for these questions, then you are missing something which no amount of political change can provide.

Quixotism may result in a lack of practicality in pursuit of one’s lofty aspirations, but Panzaism results in a lack of an appreciation for why they should be pursued in the first place. The transformation of Don Quixote’s morose and contemptuous companion Sancho Panza is not a result of external forces. It’s not that he had never been exposed to the wonder and enchantment in the world. It’s that his pessimistic cynicism made it so that he could never see it. Sancho’s prize in the end is overcoming his nihilism. And that proved to be far more rewarding than a governorship of an island could ever be.

I know this somewhat will come across as a sappy self-help homily, but it needs to be put forward:

The inherent contradiction with the Black Pill is the simultaneous realization the past is lost along with the fantastical notion it could have been restored in the first place if only "X" had been possible. People can both love their past and work toward a brighter future.; mourning has its place but is not a strategy. As a bit of a White Pill, I see this attitude growing within the Dissident Right. It won't be 1955 again, but it will be 2055, and the goal must be to create a future system that will not carry the seeds of its own destruction. Remember and love your history and people and work to honor both with a future that preserves and improves and this time endures.

<homily off>

Superb essay, as always. I really needed this one.